It started last year at the q-bio conference, which is a conference focused on

And where would you hear those words most often? Conferences, of course. In fact, you might start keeping track of how many times certain words come up, and wonder if anyone else is keeping track too...

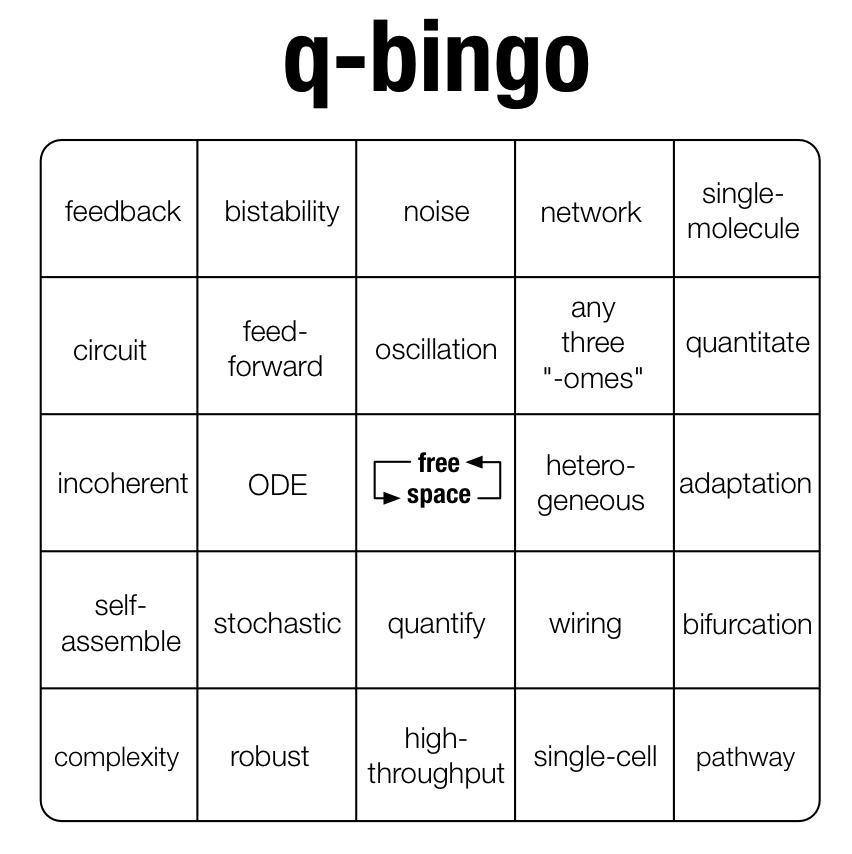

And thus, q-bingo was born. Simply cover a square whenever you hear a word used in a talk, and when you fill a straight line shout "q-bingo" straight away. Yes, right there during the talk. [Disclaimer #1: I made this suggestion fully aware that my own talk would be punctuated by a few "bingo"s. Disclaimer #2: There are other examples of such games.] Conference organizers and attendees seemed to love the idea. Sadly, the game didn't quite get off the ground due to the issue of having to print 200+ of these things for everyone at the conference.

On the other hand... At an immunology meeting, I wouldn't necessarily find it noteworthy or funny that people use specialized words like "clonotype" and "Fab fragment". So why did these words jump out at me?

- I think part of the reason is that some of these words are used to create a certain impression rather than to communicate information. For example, the word "complexity" is often to used to throw a veil of sophistication over something, without explaining what makes the topic complex. Same with "network" and "circuit", to some extent.

- Other words, like "incoherent" (as in incoherent feed-forward, which is a simple pattern of interactions/influences) can mean vastly different things to other scientists and to the general public.

- A few words aren't actually objectionable or amusing - they capture ideas that people are excited about at a particular time. There were several talks about the importance of "single-cell" measurements because of cellular "heterogeneity".

I want to hear your feedback. Are these just buzzwords, and should we try to use them less? Or are they signs of a young-ish field finding its own language? And of course... if you have ideas for q-bingo words, let me know in the comments because we might need them again this year.